How I intend to steal the Fire of the Gods and give it to the geeks.

Notice: This is a Portuguese language blog extraordinarily featuring an article in English.

As a 3D printing entrepreneur and enthusiast, I decided last year to dedicate more of my time to this transformative technology — one I believe still has its best days ahead. My goal is to go beyond prototyping and use 3D printing to manufacture final parts and components for both industrial and consumer applications.

To achieve this, I’m focusing on additive manufacturing with advanced materials like nylon and carbon fiber. Reaching extrusion temperatures above 300°C (573°F) is essential for processing these high-performance thermoplastics. This ambition makes sense, especially as engineering superplastics like polycarbonate (PC), TPI, and PEEK become increasingly accessible. These materials demand higher thermal capabilities, and the need for high-temperature hotends is only growing.

Yet, despite a wide array of brands on the market, the FFF 3D printing hotend — a critical component — remains relatively limited in both design and performance. The hotend includes a heated chamber, powered by a heating element and regulated by a thermistor in a closed-loop system. At its base, a replaceable nozzle deposits molten filament onto the print bed. (See: Anatomy of a Hotend.)

Most hotends are made from steel and use Teflon liners or titanium–copper heat breaks to manage thermal flow. Preventing heat creep — where rising heat softens the filament prematurely — is essential. This is why heat barriers and effective passive cooling are so critical: they ensure the filament stays solid until it reaches the melt zone.

Hot Ends

The standard hotend that comes installed in my Sethi 3D FFF printer—a model from the Brazilian manufacturer Sethi 3D—is a solid and well-designed component. Built from steel and featuring a Teflon lining, it performs reliably within the lower to mid-range category. It’s particularly well-suited for printing with PLA and ABS, delivering consistent results with minimal hassle.

That said, like many hotends in its class, it relies on an internal Teflon tube to guide the filament. This design works well at moderate temperatures, but the Teflon begins to degrade when exposed to temperatures above 240°C (470°F), which limits its suitability for high-temperature filaments.

Another common option on the market is the all-metal hotend—devices built entirely from metal, often featuring a bi-metallic heat break made of titanium and copper. This combination creates a thermal barrier between the heater block and the heat sink, allowing the hotend to handle higher temperatures and enabling the use of advanced, engineering-grade filaments. However, despite their design, the maximum temperatures these hotends can sustain are still comparable to standard models like the one from Sethi. Their main advantage lies not in higher heat tolerance, but in preventing premature filament softening—known as heat creep.

Frankly, it’s a bit disappointing that in 2024, the industry’s best solution for thermal isolation is still titanium—a material with a relatively low thermal conductivity of just 25 W/m·K. Surely, there must be a more effective alternative out there.

In practice, most hobbyists and casual makers hit a ceiling around 350°C (660°F). Pushing beyond that usually requires not just specialized equipment, but also a deeper level of technical know-how. Still, one has to wonder: could we one day make temperatures above 500°C (930°F)—currently the domain of high-end industrial setups—accessible to everyday users?

Rare Earths Everywhere

Over the past year, I’ve delved deeply into ceramic literature and have been consistently impressed by the remarkable objects created using various transition metals and rare earth oxides. As I reflected on the limited range of available hotend options, I began to see a promising opportunity—one that might be worth pursuing.

At its core, isn’t a hotend essentially just a glorified tube? If the team at Sethi was able to develop one using their expertise in metalworking (*), then why couldn’t someone like me—armed with a growing understanding of advanced ceramics—create a comparable solution? Why not leverage the exceptional thermal properties of these materials for what they seem naturally suited to: managing the intense heat at the tip of an extruder? It’s hard not to wonder—how has this potential avenue been largely ignored by the industry?

Ideas began to flow from some hidden corner of my mind. I started envisioning a sleek, zirconia-white form. Drawing on my experience with CAD—specifically OpenSCAD—I sat down at my workstation, the Periodic Table glowing on a nearby monitor, and began sketching out my concept: a ceramic hotend, purpose-built for my own Sethi S3 3D printer.

After a few sleepless nights, I had finalized the blueprint for my petite yet bold creation—one that broke away from the conventional stacked-disc design of typical metal heatsinks. Its form was unconventional, shaped by the unique properties of ceramics. With significantly lower thermal conductivity, ceramics eliminate the need for large heat dissipation surfaces, opening up exciting possibilities for more compact and creative designs. Add to that the material’s texture and color versatility—imagine a soft pink version for March—and the result isn’t just functional, but beautiful. A hotend, reimagined as an object of both engineering and aesthetic value.

Within just a few days, it became clear to me why ceramic objects—beyond toiletries—are so rare in the market. This realization also highlights the thoughtful and highly relevant design of the original hotend envisioned by Sethi in 2013. Traditional ceramic shaping methods simply don’t accommodate elaborate stylistic innovations or intricate anatomical details.

Until recently, advanced ceramists lacked the technology to break completely from traditional methods, restricting them to producing relatively simple forms—like rings and tubes—using techniques such as slip casting, pressurized injection, and dry pressing. These large-scale industrial processes limited design complexity. For a small, precision component in a device like a 3D printer, ceramics have historically seemed impractical.

Sol-gel Comes for the Rescue

Sol-gel chemistry, a process I had studied extensively in the months leading up to my insight, presented a promising solution to the challenge of working with ceramics in fine mechanics—enabling the creation of ceramic objects with remarkable structural complexity.

Simply put, sol-gel chemistry involves synthesizing inorganic polymers or ceramics from a liquid solution. This process begins by converting liquid precursors into a colloidal suspension called a “sol” (from SOLution), which then transforms into a three-dimensional network known as a “gel.”

The formation of a sol results from hydrolysis and condensation reactions of particles, creating a colloidal system—a dispersion of tiny particles within a medium. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a colloidal system is a dispersion of one phase into another where, “the molecules or polymolecular particles dispersed in a medium have, at least in one direction, a dimension between 1 nm and 1 μm”. Everyday examples of colloids include milk and mayonnaise.

The sol-gel process has been extensively studied and applied in advanced ceramics; for deeper insights, I recommend consulting the specialized literature. For instance, the ceramic tiles covering the space shuttle’s heat shield are produced using techniques closely related to sol-gel chemistry.

Gel Casting

Ceramic shaping techniques generally fall into two categories: dry and wet forming processes. Gel molding, also known as gel casting, is a wet forming technique. The technology we employ—developed by Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL)—allows for the fabrication of high-density ceramics with intricate, near-net-shape geometries. This method offers several significant advantages, including fast molding cycles, no limitations on mold materials, excellent mechanical strength in the unsintered “green” state, and the capability to produce components with varying section thicknesses.

It’s important to highlight that the gel molding method permits the use of virtually any material to shape ceramic masses, unlocking vast new possibilities for 3D printers. No longer confined to prototyping, these printers can become powerful and efficient tools for manufacturing advanced ceramics, thanks to their ability to produce complex molds directly and affordably on-site.

This potential extends to FFF printers as well. In gel casting, the unique layered texture of the printed mold is faithfully transferred to the ceramic parts. I personally intend to embrace this “imperfection” as a distinctive visual signature that reveals the product’s origins. Naturally, others may prefer molds that are flawlessly smooth and uniform—whether created via SLA, SLS, or precision-machined from stainless steel.

Overall, integrating gel molding into FFF printing represents a major leap in productivity and profitability. An ABS mold that takes just two hours to print can be used to replicate thousands of high-performance ceramic parts in a remarkably short time.

This Project

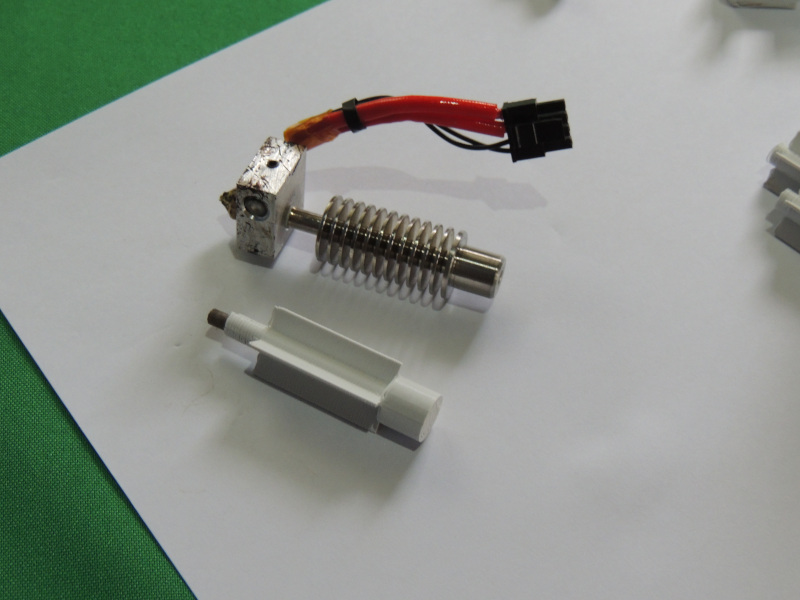

Our process begins with preparing water-based gels by dispersing ceramic powders—such as zirconia and yttria—in water. We then add gelling agents, including monomers and initiators, and mix thoroughly to form a stable colloidal suspension, as described earlier. This slurry is poured into an ABS plastic mold created via 3D printing and allowed to dry, forming a “green” ceramic body.

Once dried, the green body is carefully removed from the mold, subjected to further drying, and then sintered at high temperatures to achieve full densification. The final steps include precision machining and partial enameling to complete the component.

Until recently, acrylamide (AM) was the standard gelling agent used in gel molding. However, its neurotoxic properties limited the widespread industrial adoption of this technique. This constraint hindered the development of gel molding and contributed to the relative scarcity of complex ceramic objects on the market. In our project, we employ a gel shaping process using natural polymers such as agarose, effectively removing these barriers and unlocking the full potential of the technology.

It’s almost poetic that a material as ancient as ceramics remains one of the most advanced in terms of performance. While I may make it sound simple, reaching this point required months of both theoretical study and hands-on experimentation.

The result is an innovative product: a compact thermal element weighing just 10 grams. Despite its delicate appearance, it can withstand temperatures above 2300°C (4300°F) while transmitting only 1.7 W/m·K of heat. For context, titanium can endure similar temperatures but has a much higher thermal conductivity—about 25 W/m·K. Teflon, on the other hand, is an excellent insulator at just 0.2 W/m·K, but it breaks down at around 240°C (470°F). The zirconia–yttria ceramic system we’re using offers the best of both worlds: extreme heat resistance combined with low thermal conductivity—ideal for mitigating heat creep and enabling reliable extrusion of virtually any filament.

There are other advantages too: the process is energy-efficient, completely silent, and produces no significant waste or emissions. And again—this component weighs just 10 grams.

In the second phase of the project, we plan to integrate a zirconia–magnesia heatbreak into the ceramic body, further strengthening the assembly. From there, the only real limit will be what the hot block can endure. I recently came across a Japanese research group developing a hotend for temperatures around 850°C (1600°F). Suddenly, the idea of extruding copper wire on my Sethi desktop printer doesn’t feel like science fiction—it feels inevitable.

But this is where the problems begin.

Tests

At this moment, I find myself surrounded by newly acquired lab equipment—beakers, Erlenmeyer flasks, precision scales, a magnetic stirrer, and a range of chemical substances. What was meant to be the humble beginning of a small-scale industrial project could easily be mistaken, depending on who walks in, for a pharmaceutical lab or a customs rapid-analysis room.

I’m on the verge of a critical phase: validating whether the process described above can perform reliably and repeatedly at a production scale.

Beyond the formal process and the few prototypes we’ve created using individual molds, a rigorous series of tests still lies ahead. These include experiments on chemical composition, formulation refinement, and destructive testing for mechanical, thermal, and functional performance.

If we succeed in producing a reasonable quantity at a reasonable cost—and I’m confident we will—the product will be made available for direct sale on the soon-to-launch Triforma website. The business model will be inspired by that of Slice Engineering, with an emphasis on Open Source licensing.

My target is to have a minimally viable product ready by mid-April. Until then, I’ll be working relentlessly toward that goal.

I’ll be sharing updates and results here—stay tuned.

(*) A note on Sethi 3D:

Though I’ve mentioned Sethi 3D several times, I want to clarify that my only connection to this respected company from Campinas, Brazil, is as a [very satisfied] customer. That said, I’d be thrilled to collaborate with them in any capacity. I hold deep admiration for industrial ventures in advanced technology—especially those based in Brazil, where such efforts deserve not just respect but real celebration.

Recommended Reading:

Sol-gel

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sol-gel_process

Sol-Gel Chemistry and Methods

Gel Casting of Ceramic Bodies

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118176665.ch6

The evolution of ‘sol–gel’ chemistry as a technique for materials synthesis

https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2016/mh/c5mh00260e

Thermal Properties of Ceramics

A review on aqueous gelcasting: A versatile and low-toxic technique to shape ceramics

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272884218334606